Warning: prepare to cry. I weep as I bare witness to this unimaginably tragic refugee crisis each day – and wail as I relive and process its gravity in my mind, through words, and on paper. I endeavor to be strong, but today, I failed. Though I affirm that even in the face of death, miracles happen. I know not how, but light will prevail; it must.

A boat with 300 refugees sunk before my eyes. Blood poured from the lips of a baby whose face was grey. A mother wept unable to find a single one of her five children once ashore.

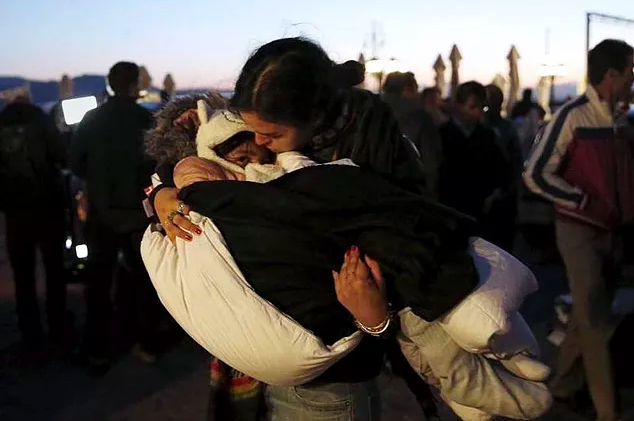

A father cried in ecstasy when he raced over to find that the child in my lap was in fact his son, Mustafa. A severely hypothermic man came back to full consciousness with my body pressed against his lying on the docks. Joyous smiles were rampant aboard the buses to camp in this new land of promise.

The lowest lows and the highest highs. The all-consuming pit in my stomach and the tingles throughout my soul. The dichotomy of life here on Lesvos, where thousands of refugees came ashore once again today – and sixty human beings are presumed dead from the largest maritime disaster in Greece in years, which still does not make the news… or only a local Greek paper, as I shared in my last post an accidental find for which the photo in the article is somehow of me with a darling girl Mina in my arms, a bizarre discovery to end this horrific day.

[Please note: I write these posts from the first person, to share my truths, to tell you one point of view, to capture experiences, to offer a personal perspective, not to center any part of the narrative on myself; I am but a servant, a messenger, a vessel and I hope that sentiment comes through sincerely.]

Today began with a drive to the north of the island, past the warehouse where we stocked our car with massive quantities of dry socks, baby and children’s clothing, shoes, hats, blankets, anything we could fit in the trunk – because we need all seats available for when we must switch into full ‘shuttle service’ mode. And a lot of people can fit packed into our backseat! We passed a steady stream of refugees heading in the opposite direction on the main road, toward Oxy transit camp. I waved and smiled, as always – which delightfully changes the whole tone of our driveby encounters – but this time, I really stared into their faces. Most of those who make the multiple-hour trek on foot, as opposed to waiting out the bus or being transported in smaller cars, are younger able-bodied men. These looked like people I went to college with, walk past on the sidewalks of New York City, elbow in a busy airport terminal or shopping mall. I was taken aback.

We then started on the dirt road – winding up, down, and around the mountainous coast. This is the first section of the trek that refugees have to make on foot once successfully coming ashore here on the Greek island, many without shoes (often lost at sea or the jarring waves during landing), in sopping wet clothes, carrying small children, and shouldering heavy waterlogged bags with all their worldly possessions. There are simply not enough vehicles that can manage these rugged dirt roads, and certainly no large ones until the final paved section before camp, and even then, too few buses means many walk. These journeys are against all odds every single step of the way.

I pointed to the horizon line at one point, thinking I spotted an orange mass in the distance, not far off the Turkish coast; that is how boats appear, as they are typically nothing more than loads of people in orange life vests packed atop a rubber dinghy. Then less orange was visible; I cast that off on the particularly turbulent waters. Then the orange seemed to disperse. We stopped the car at a lookout point. A woman standing alone with a solemn look confirmed my worst thoughts: the boat was sinking. I asked what we could possibly do, “Nothing. Just pray," she answered with a harrowing truth, saying that she had just rang the coastguard. Within two minutes, a crowd of twenty had amassed at the spot where we stood – doctors, aid workers, volunteers from Denmark, England, Greece, the US, Germany, Britain, Jordan, all over. We watched earnestly as a Norwegian boat sped towards the shipwreck, though nowhere near fast enough, followed later by a Greek coastguard ship with two jet skis. I peered through binoculars, watching as the dinghy was lowered into the water to begin the rescue operations, people floating further and further away from each other with each passing moment. I could not fathom what was unfolding before my very eyes: people were dying and there was absolutely nothing that I, or anyone else, even the highly trained doctors and medics by my side, could do in that instant. We stood helpless on a cliff, ghastly white, in shock. Forgive the melodrama, but this reality is grave.

Our group disbanded, once word reached of another damaged boat coming in – with two more nearing different points on the shoreline. We headed towards a far-off one, driving our little car over sharp rocks until we were a few yards from the refugees flooding onto European soil. One boy caught my eye, tears streaming down his face and he clung to his mother. He was drenched, so I beckoned his family to follow me to our car, where Jodi dressed them in the most adorable of outfits, bundled up from head-to-toe. Immediately upon my approach, the mother had handed me a newborn, begging me to warm her daughter. I sat with the less than one-month-old girl in my arms by the car heater, staring at her precious sleeping face and long eyelashes – attempting to imagine what it must take to be compelled to pay a smuggler for an illegal rubber dinghy crossing across treacherous waters to an unknown land WITH your tiny little fragile baby! Oh, life. We packed the entire newly arrived Afghan family into our car for the drive over the mountains to Eftalou to catch the bus; mother, father, brother, baby sister, aunt, and cousin, as well as Jodi and myself and ample bags and boxes fit without worry.

We continued onwards toward Molyvos just before sunset, knowing that the coastguard ship with rescued refugees would soon be arriving in the harbor – and there it was, pulling in as we arrived. The scene was pure pandemonium, ambulances waiting with open doors, doctors poised with stethoscopes around their necks, and many volunteers standing with mylar and emergency blankets, as well as heaps of dry clothing. We jumped right in to lend a hand, for operations here on Lesvos always need more volunteers (remember that, those who are considering making the trip!). I honestly cannot even tell you what happened with the first boats – people, bodies, screaming, shouting, oxygen tanks, crying, wetness. Chaos. Survival mode. I was at one point tossed a girl, a small child with wet curly hair and a look of sheer terror across her face. I held her tight and, with the help of two brilliant young Brits (who had clearly never been tasked with the responsibility of carrying for a child, let alone changing a terrified, soaked girl), got her out of her clothes and into a new diaper, many many warm, dry layers, topped off by an adorable fuzzy bear hat with ears that doubled as mittens. In my broken Arabic, I got that her name was Mina, she was 3, from Syria, and had come over with her mother Sarad and father Muhammad, though they were not with her when she was passed off the ship. I wrapped her in a quilt and set out looking for her parents, navigating the mad crowds and makeshift emergency medical setups while singing to and tickling the little lovebug in my arms. I am beyond delighted to report that after an hour or so of walking and asking for Sarad (not Muhammad, as that is the most common name around!), we found her! The mother wept in gratitude, uncertain as to whether her daughter had made it onto that ship, or any other one, alive. Miracles happen!

As the next boat came in past dark, we all knew the passengers would be in even more dire straights and braced for the worst, calling in additional doctors from anywhere around the island. Babies came off first, CPR was happening in too many places to count, every oxygen mask was in use, blankets upon blankets were layered on hypothermic individuals. The chaos intensified. One man was borderline unconscious from extended exposure to extreme cold –, a doctor hunched over his face, constantly monitoring his levels (I am not medical, so I cannot tell you which exactly, but they were alarmingly low), but sometimes he would shake or shiver, a good sign, I was told. A medic was rubbing his body vigorously through mylar blankets and asked me to help, so I dropped to the ground immediately. I remembered once hearing that body-to-body contact helped people when they reached such states and asked the doctor, who responded with a resounding yes… so I ripped off my jacket and me and my cotton top and bare skin got under the covers to embrace this freezing cold man. We all continued trying to heat him, as his body began responding more and more, until he was able to open his eyes and mutter sounds, then be carried to a nearby chair to continue to warm up. Miracles happen!

It was long after dark when the final boat rolled in, some of these people having been in the water for over five hours, one told me. I stood to the side, making way for the medical professionals to deliver the life-saving services they do so well. But then hopped aboard with a rather crazy leap, to warm one man who stood trembling, shaking, quivering and cover him in blankets, before we could take him to shore. I was called back, as a woman who collapsed in the rear had screamed in protest when two men tried to remove her saturated layers of clothing. She let me, another woman, rip if off and bundle her in blankets, unable to stand, frigid to the bone. We took her off of the ship right behind a 350-plus-pound man, who was carried by six strong men. He had bloody scratches and burns all over his limbs and head, the result of being hoisted out of the water via rope, the only way that the coastguard could manage to save his life. The man was stripped, laid on the ground, and covered in at least nine blankets. He did not need medical attention, they said, but would be hurting from his superficial wounds for a while yet – and was impossible to move any further due to his sheer size and weight. So I sat with him and had one of my most fascinating encounters to date.

Okba Badr is a middle aged physiologist from Homs, Syria who left his country for Jordan, where his wife and son remain, then took his mother to Saudi Arabia, before beginning a journey through Egypt and Turkey to that doomed boat journey to Greece. His English consisted of a few hundred words and my Arabic tops off at a couple dozen, but somehow we managed to communicate quite effectively – and our conversation kept his mind off the pain. When he found out I was American, he told me that he did not approve of our president – through grunting and hand gestures (which were critical enough to his point that he dare remove his limbs from beneath the blankets, also a sign that he was warming up!) about Barack Obama, President Assad, and ISIS. “Obama. Pshh. Bashar. Pft. Da’ish. La’a.” Translation: no thanks, disapproval, nope. He went on to say that Obama should take a stronger stance against ISIS (Da’ish is the Arabic acronym for the terrorist power) by gesturing that Obama coming in to take out ISIS would be a very good thing, but that he will not do it. I inquired as to his opinion of Putin. An absolute NO! He added Germany and Turkey to this world leader ranking on his own accord: “Merkel? Good. Erdogan? Yes.” "Cameron?” I probed. “So-so,” he waved his hand back and forth in reference to the British Prime Minister. “Bush. Bad,” he proclaimed of George W. "John Kennedy,” he said with a big grin, “very good.” “Hillary Clinton?” I added. “Maybe,” he said while nodding, “Lady!” Our discussions were marvelous and lasted for hours, much to the amusement of passing by doctors, translators and aid workers. I loaned him my phone to try to Facebook family with news of his arrival/survival, as his phone, like nearly all other possessions of everyone on that ship, had been lost at sea. When all other patients had been handled, Okba was very delicately moved into the church next-door, which the local townspeople had graciously opened for the first time EVER, after death quite literally arrived at their doorstep. I hugged him goodbye, knowing that we would always share that special bond.

I headed over to The Captain’s Table, the restaurant at the end of the harbor, which acts as HQ for a group now known as Starfish (more on them later this week, when their website launches!), coordinating efforts on the north of the island more than any other entity – and certainly in charge of what goes on in Molyvos. Jodi had been back and forth between there, dressing the kids and mothers and other refugees who did not need serious medical attention, and the dock, where she was Periscoping as the situation unfolded. I heard news swirling that another coast guard boat had come into Petra, a nearby town, with over a hundred people from the same shipwreck, but didn’t have it confirmed until I arrived there. Ninety plus people were en route to Molyvos, the rest having been taken by ambulance directly to the hospital in Mytilini. We needed drivers to take passengers from the bus at the top of the hill down into the harbor, where they would receive dry clothes and shoes, basic food (bananas and chickpeas), water, ample blankets, and a roof over their heads to sleep until the buses would come tomorrow. So I hopped in my car. One volunteer asked if I could take the “alone children,” named such because we did not know where their parents were and if they had survived. Many parents were desperately seeking their children; two had been wailing nonstop for hours, one woman missing all five of her daughters and the other unsure of the fate of her two little ones. My heart ached as I hugged each, loaded the toddlers into my car, turned on the heat, layered them in clothing, offered up water, and drove these four precious souls down the hill: Muhammad, Mustafa, Najib, and Alah. We sat down in a corner table outside of The Captain’s Table with two other kids, needing to keep these children together for processing by the NGO responsible for orphaned minors, if in fact that was the dreadful reality – or, on a positive note, to bring parents over to see if their children were a part of this newly arrived busload. That was the delightful case for many, including Mustafa, whose father came running over, swept up the sleeping child from shoulder, and kissed every inch of his face, as the boy woke up and hugged his baba exuberantly. Every single person who witnessed that encounter wept; you cannot help but feel pure happiness in such an unlikely and all-important reunion. Miracles happen!

Muhammad remained on my lap, eating two entire plates of french fries, at least six slices of bread, and no less than three bottles of water; he is but three-years-old! After his feast and cozy new jacket, I made a bed of blankets for the bleary-eyed angel where he quickly dozed off. I then set to finding shoes for two other “alone children,” Ibrahim and his sister Sara. The thirteen-year-old boy (with green braces!) and twelve-year-old girl spoke English better than some of the translators, articulate and polite. They were making the journey from Damascus, Syria with their father, mother, and six and two-year-old bothers, none of whom have been located since the shipwreck. I asked where they were headed. “I don’t know. My father has the plan,” Ibrahim told me, clearly not allowing the devastating thought of fatalities to cross his mind. How could you? How could you even begin to imagine that your entire family is dead – leaving you alone with your little sister in a foreign country without a clue as to what comes next? Horrific.

I almost took little Muhammad home with me for the night – I wanted to – but made everyone there promise me that he would receive nothing but the finest care and attention in my absence. And off we went… not before five young Greek men physically lifted the car, yes lifted and moved it two feet, to make it possible to get out of the tight spot. Crazy. On the ride home, Jodi told me of a riveting conversation she had with one refugee, Ramzi, who asked to use her phone. He broached the question by saying that he would pay to call his father to tell of his safe arrival. She refused payment and let him use her phone. Ramzi kept telling her of his wealth, that he studied in Dubai and was staying at a hotel in Mytilini (instead of the refugee camp in Lesvos’ port city). The entire family had fled Syria except his father and one brother, because if all were to leave, they would lose absolutely everything – and their land holdings and wealth are of considerable valuable. What a complex web! Ramzi also told Jodi the tale of today’s crossing. This boat was not a rubber dinghy like nearly all that make the sea journey; this was a 300-person wooden “yacht” of sorts (there term which Ibrahim also used in reference to the vessel). The smuggler captained the ship initially, then had another boat come to return him to the Turkish shore, but that carelessly crashed into the side of the already rickety refugee boat at a precarious point, causing it to split and the roof of the second deck to collapse, killing some passengers upon impact; others died in the water before the coastguard reached the distant Greek waters – all of this according to the twenty-something Syrian survivor.

242 refugees were rescued in total; the rest are still formally only ‘missing,' though one member of the coastguard said that he left behind “tens and tens of dead bodies floating,” to use his precise words. The ultimate risk that these individuals take in leaving Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq became all too real with this shocking loss of life.

I’m wrecked, I’m drained, but I am alive – and for that, I am profoundly grateful. I am also blessed to be here right now and to share love and hugs, smiles and tears with such brave, beautiful souls.

Comments